Elisa Martins

Journalist, special for Yvirá

Giselle Soares

Journalist, Rede CpE

Elisa Martins

Journalist, special for Yvirá

Giselle Soares

Journalist, Rede CpE

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2025 | N°3 | YVIRÁ brings together experiences that can help address the challenges to classroom flow, learning, and well-being in the school environment

The use of cell phones in the classroom, despite its legal prohibition in Brazil , is one of several manifestations of indiscipline that increasingly challenge educators. Interruptions, side conversations, and aggression have also been exacerbated in a highly connected and distracted generation. Although there is no single solution for dealing with these behaviors, sharing experiences can serve as a basis for best practices. YVIRÁ has gathered some of them.

“Students need to know what is expected of them and the consequences of their actions. Ideally, these rules should be developed participatively, with the collaboration of the students themselves, increasing their sense of belonging and responsibility,” says Sheila Garbulha Tunuchi de Campos, a teacher of educational projects (Reading Fluency, Body Practices, and Social-Emotional) in the municipal school system of Porto Feliz, in the state of São Paulo.

Creating a positive bond between teacher and student, she states, is the foundation of any mediation. Empathetic educators, who practice active listening and demonstrate genuine concern for their students’ development, inspire greater respect and collaboration: “Valuing students’ efforts, even in small achievements, also strengthens this bond and fosters a more positive environment.”

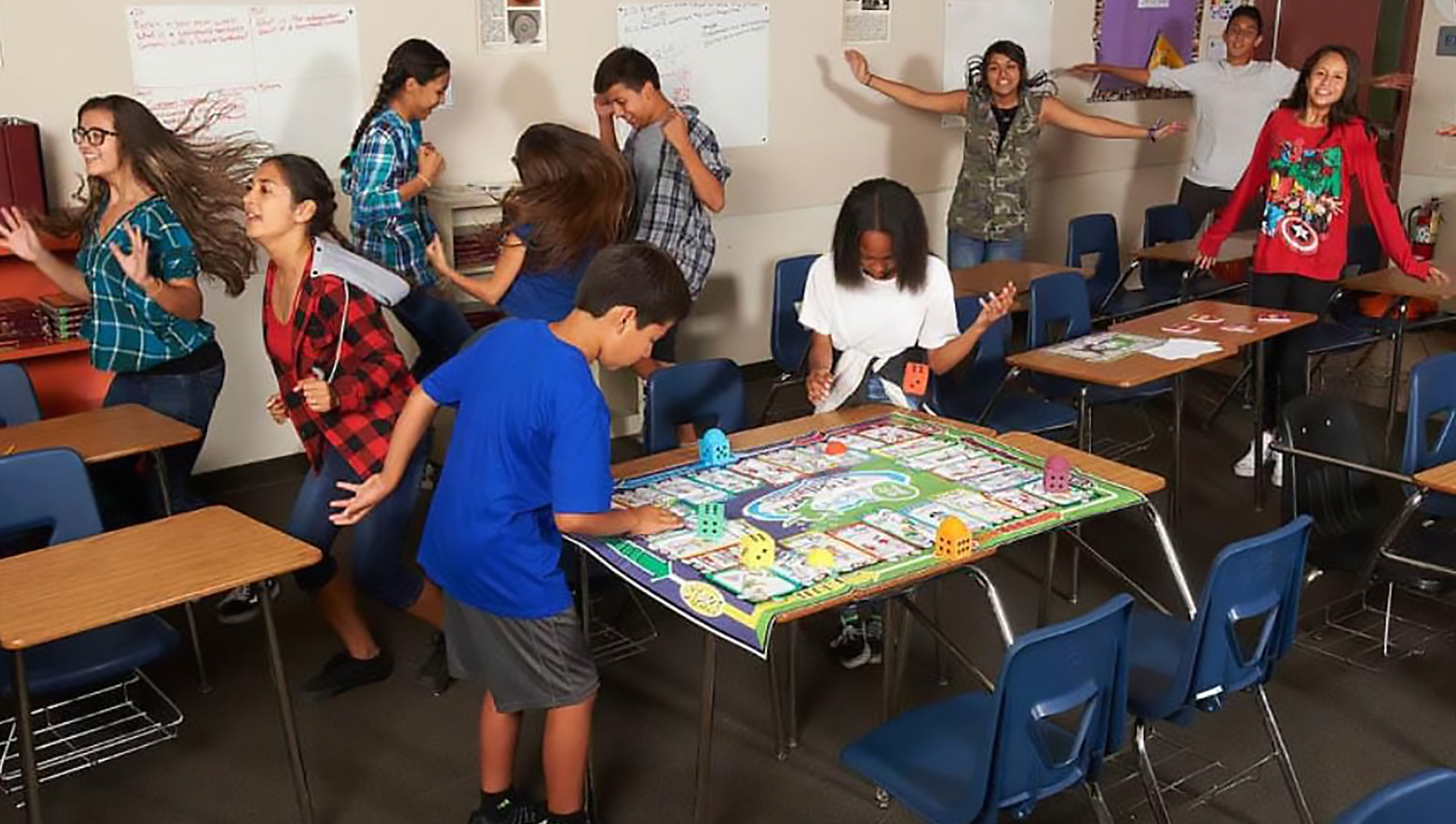

Social-emotional activities are proving to be powerful tools. The educator cites the “Socio-Emotional Rescue” project, implemented at a municipal public school in Porto Feliz, which emerged from observing the behaviors of children aged 6 to 8, who were babies at the time of the pandemic. “The activities included dialogue circles and active listening, which set aside weekly time for students to express feelings and opinions in a safe environment, with a focus on empathy. Through cooperative games, we promoted collaboration and teamwork, strengthening bonds and teaching respect for differences,” says Sheila.

“A Code of Coexistence was also created by the students themselves, which collectively defined values and behaviors, strengthening responsibility and autonomy. Mindfulness and relaxation classes helped manage stress and anxiety, and increased concentration. Finally, the so-called ‘gratitude mail’ was a space for anonymous messages of gratitude, promoting the appreciation of relationships and mutual respect,” says the teacher. “Often, this break from traditional content to rebalance the classroom or school is worth it.”

Body and Speech

Attention to the environment makes a difference. After all, it’s in the same busy space where students interact with peers, exchange experiences, explore creativity, and navigate differences that issues of relationships and behavior arise, recalls Karinne Rodrigues, a literacy teacher in the municipal public school system in Ouro Branco, Minas Gerais.

The school where she works focuses on activities that foster respect, listening, and prior knowledge of students and their cultural capital. Karinne mentions the “Class Assembly,” a tool aimed primarily at first-grade students, ages 6 and 7.

“It’s a pedagogical approach that gives students the opportunity to share their perceptions about rules of coexistence and interpersonal relationships with the group and, collectively, discuss possible solutions to certain situations,” she explains.

Since the beginning of the school year, students have been jointly defining which rules of coexistence are essential for a respectful and productive environment.

“It’s an activity that contributes to the (de)construction of the term ‘indiscipline’, to a more appropriate definition of what the body and speech convey when a child isn’t feeling well,” says the teacher.

“By viewing indiscipline as a form of communication for children, a cry for attention, an unspoken discomfort, or even a search for belonging, we can transform everyday challenges into learning opportunities,” says Karinne.

Gesture of Hope

Talking about indiscipline and disrespect in the classroom also means recognizing the complexity of the relationships woven into everyday school life. For Gabriela Arruda, pedagogical coordinator of early childhood education at a private school in São Paulo, the experience taught us that the authority that transforms isn’t the one that imposes, but the one that’s built through relationships with students.

“Instead of controlling a child’s body, we need to ask ourselves: what does this body mean? What kind of environment are we providing so that they can exist with dignity, movement, and voice? We need to view the classroom as a space of liberation, where affection is a political practice. A child who throws themselves on the floor, interrupts, and doesn’t ‘respect’ the circle may be trying to survive in a space that doesn’t listen to them. That’s why, before labeling, I observe,” she says.

A few years ago, she recalls, a child who frequently screamed and pushed his classmates ended up showing that the classroom needed more space for movement. A reorganization was carried out, including a rolling mat, stacking blocks, and a ramp. The child started running less, says Gabriela, because he no longer needed to run away.

“There’s no manual, but a compass: a scientific and humble perspective. This doesn’t mean there’s no limit. Limits are fundamental, but they only make sense when they have a clear purpose and are born of mutual respect,” she says.

Some of the actions include group agreements, honest conversation circles, space to name feelings, and giving time to time.

“Once, in an older class, we created a mural with the question: ‘How do we want to feel here?’ The answers were touching: safe, free, happy, listened to. From then on, each conflict situation was revisited in light of these collective desires,” recalls Gabriela.

Of course, there are difficult days, when tension rises, fatigue weighs on us, or the student repeats aggressive gestures, despite all the precautions. “In these moments, I breathe. And I remember that no gesture of mine should be greater than what I want to teach. If I want them to learn respect, I need to respect them. If I want them to self-regulate, I need to self-regulate,” he says. “It’s not easy, but it’s not impossible. I continue to learn with each child, with each challenge, and, above all, with the certainty that education is a radical gesture of hope.”

Moments of Reflection

If dealing with indiscipline is inevitable, encouraging students to reflect on it is a good bet. “Behaviors are more complex, and this isn’t due to a widespread lack of education. We’re facing the challenge of a generation of students exposed to many visual stimuli and learning methods, while there’s also a disbelief in the formative role of schools,” says Daniel Bahiense, a high school teacher and pedagogical coordinator in Rio de Janeiro’s private school system.

“Investing time in individual and group conversations creates great possibilities for transformation. The older the students, the more we invest in this,” he says.

In the case of high school, he says, the school encourages students to reflect on ethics alongside teachers and on how individual actions also impact others.

“We can’t have a situation where a teacher wants to teach and the students don’t stop talking, and another student who isn’t talking thinks it doesn’t concern them. We need to be more sensitive and critical,” says Daniel. When situations like this arise, he says, individual conversations are held, and collective ones too, with entire classes immersed in assemblies and debates on topics that need to be understood as common challenges.

“Sometimes, we fail. Education has this; it’s not a manual. Often we need to stop, discuss, return to the same topic several times, and demonstrate that dialogue is taking place. It’s not just a matter of issuing a warning, suspending, and stopping there,” he says.

The challenge goes beyond teachers and the school: “The school needs to engage with the most contemporary developments in the field of education and pedagogy. But a collective renegotiation is also necessary regarding the role of this school, which is still very important in the ethical and civic construction of respectful relationships. What happens at school is everyone’s problem.”