Natália Mota

Instituto de Psiquiatria

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

Social cognition demands a large investment that pays off in the end. To make sense, this adaptive learning carries marks of the social environment in which each person grew up.

Being alone in the lion’s savannas was not good at all. It’s as if this constant fear of survival pushed us towards the opposite effect, amplifying the immediate and more primitive response of the initial programming.

At school, the child trains and creates their social skills in an increasingly independent and autonomous way from their family. They make their choices, test their ideas.

Just as we control infectious diseases more with hygiene than with antibiotics, we need to think about attitudes that promote true “mental sanitation” in school environments.

FEBRUARY/MARCH 2026 | nº5 | Just as the causes of the problem can be social, responses must aim for increasingly healthy environments and communities

Natália Mota

Instituto de Psiquiatria

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

IMAGEM: ADOBESTOCK

Mental health, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), goes beyond the absence of disorders: it consists of dealing with challenges and remaining productive, learning, and contributing to the community. This means that, throughout development, an individual builds a foundation that allows him to make assertive decisions, create and maintain healthy relationships, contribute to the community, and learn from it how to adapt to their own and collective challenges. It is a topic that is broadly related to a better school environment, and this article aims to clarify why.

This sense of collective learning is important because we are extremely social beings. If we stop to think about what made a medium-sized primate without large fangs or claws become so successful surviving in the lion’s savannas, we won’t be able to understand it by looking only at the individual. It’s because this primate developed such sophisticated social skills that it became capable of forming cohesive groups to solve its problems. To this set of skills, we have the construction of social cognition (a set of cognitive skills such as expressing emotions and recognizing those of others) which is fundamental to building mental health.

Social cognition demands a large investment that pays off in the end. To make sense, this adaptive learning carries marks of the social environment in which each person grew up. It is a long process characterized by the social responses that occur throughout everyone’s life. For this very reason, these are skills that require a lot of time to develop, socially, psychologically, and neurobiologically.

Fear and Learning

These skills become increasingly sophisticated as we learn from experiences, mirroring the neurological maturation that is only completed at the end of adolescence. This slow development helps us adapt to everyone’s environmental conditions. An example is emotional reactions. We are born with a very primitive system for perceiving emotions (the limbic system). It ensures our survival with very immediate reactions to sensations such as fear, for example.

Social cognition demands a large investment that pays off in the end. To make sense, this adaptive learning carries marks of the social environment in which each person grew up.

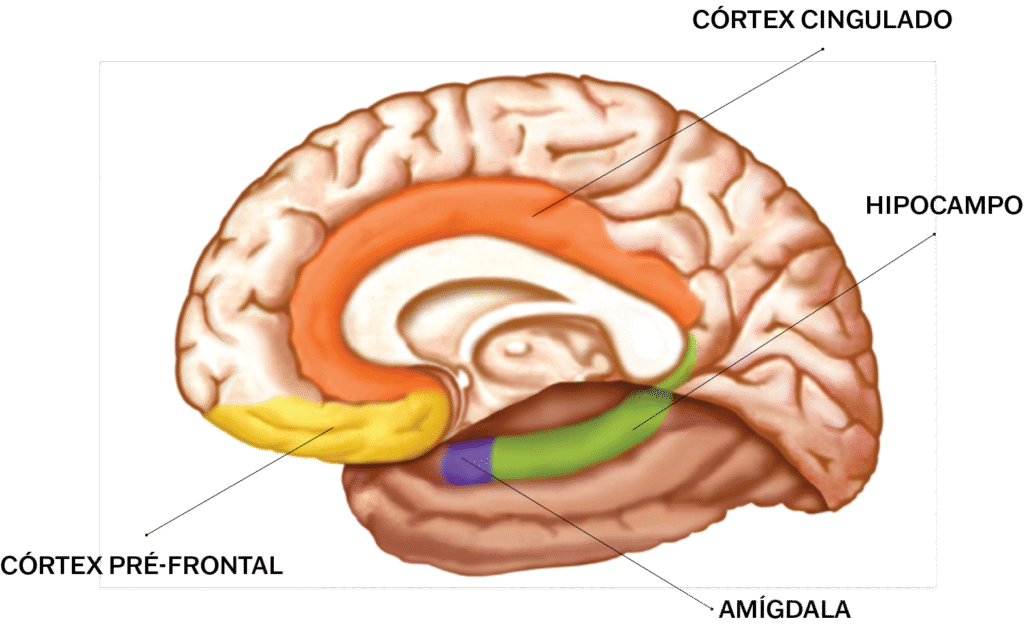

Regions that are part of the limbic system or are connected to it.(Image taken from the book “One Hundred Billion Neurons?”, by Roberto Lent)

We live and experience fear in various situations, and through development we learn that we can recognize fear without running away or fighting to defend ourselves. The more we communicate with more experienced individuals in this social environment, the more we learn to have more adaptive recognition and reactions to the challenges of that environment. This generates learning and helps connect the limbic system (a network of regions linked to basic emotions) with much more sophisticated cognitive processing structures, such as the prefrontal cortex.

The more we talk and solidify this functional learning, receiving good responses from the community, the more we feel like we belong, integrated, and this is fundamental for our species. Being alone in the lion’s savannas was not good at all. It’s as if this constant fear of survival pushed us towards the opposite effect, amplifying the immediate and more primitive response of the initial programming. Beyond that, the more we train and understand more functional and less immediate or obvious responses to emotions, the more we engage inhibitory control and rationalization, managing to have the calm to think before acting.

In neurological terms, the full development of these skills takes several years to happen, maturing only at the end of adolescence, around 24 years of journey. Here when I refer to maturation it would not only be in the psychological sense, but a biological development as well. This is because the maturation of very sophisticated brain structures is necessary for this.

Being alone in the lion’s savannas was not good at all. It’s as if this constant fear of survival pushed us towards the opposite effect, amplifying the immediate and more primitive response of the initial programming.

Individual Development

The problem is that in adolescence we have an ungrateful situation on this journey of neurobiological development. This period, which begins in puberty, is marked by an initial maturation of the limbic system, allowing the perception of increasingly complex emotional situations, but the maturation of the prefrontal cortex (marked in yellow in the figure above) and the complete myelination of its pathways will only be completed at the end of adolescence. In other words, we spend at least 10 years feeling the world with great intensity, but still without the structure to understand so much emotion. If this social environment is very challenging, if there are no communication resources, nor a sense of belonging to the community, the scenario can be even more difficult.

It is here that I reflect with you on the much broader role of the school in the development of individuals. At school, the child trains and creates their social skills in an increasingly independent and autonomous way from their family. They make their choices, test their ideas. In adolescence, this process deepens through the search for identity, often experiencing identification with different social groups.

This can happen by observing the way they dress, the music they like, the ideas they spread. This is the time to fly out of the nest, to test their way of thinking about the world, listening much more to their peers, often abruptly detaching themselves from the most secure family ties. The point is to remember that the limbic system is processing a lot of emotions that are difficult to understand, which can generate a healthy identification with a group, or not.

Let’s take as a hypothetical example a boy who begins to feel attracted to the girls in his class but is too insecure to deal with it. In his shyness, he chooses not to talk to classmates who know them, and prefers to seek information on social media, finding boys who blame those girls they don’t even know for the discomfort and insecurity they experience. Anger becomes associated with this attraction, and that boy, who hasn’t even tried to have an experience with anyone yet, already begins to feel something that can evolve into misogyny, that is, feelings such as anger and even hatred for the condition of being a woman.

These social constructs can lead to various relationship difficulties, including a predisposition to violence against women, bringing consequences for girls and women with whom he may have relationships, but also for the individual himself, who may isolate himself and find it increasingly difficult to experience a healthy sexuality. Such factors contribute significantly to the emergence and exacerbation of mental disorders.

At school, the child trains and creates their social skills in an increasingly independent and autonomous way from their family. They make their choices, test their ideas.

Much earlier

Since 2010, the academic community has been pointing with great concern to the growing epidemic of mental health problems occurring at increasingly younger ages. Until 2010, the prevalence in this age group was around 10%. Today, it is at 30% in most countries that collect this data, reaching almost 50% (half!) if we look at North American data with a gender breakdown (in girls). Currently, the peak of symptom onset is around 15 years of age. What could explain this abrupt increase?

Understanding that mental health problems are multifactorial, often resulting from genetic vulnerabilities that are expressed in adverse environmental situations, since 2010 there has not yet been enough time for us to have changed the genetic vulnerability of the population globally. This then leads us to look at potential social causes.

In the last decade, we have had profound changes in technology-mediated socialization. Social media makes exposure to highly emotional content (to generate engagement) accessible and unregulated, often spreading dysfunctional and distorted thoughts about reality. If this situation is already bad for adults, imagine the consequences for those who do not yet have the necessary neurological maturity to truly reflect on it.

Furthermore, we are experiencing global challenges that impact this generation with even greater strength: profound climate change, wars, and precarious working conditions, fostering an environment of insecurity and uncertainty. All of this leads to a profound increase in hopelessness about the future, especially for those who have their entire future ahead of them.

Thus, just as the causes must be social, the responses must also be in this sense, that is, amplifying the vision of prevention and promotion of mental health by targeting increasingly healthy environments and communities. The proposal is for a very careful look at the school environment. Just as we control infectious diseases more with hygiene than with antibiotics, we need to think about attitudes that promote true “mental sanitation” in school environments.

Promoting safe environments to talk about emotions, providing information on psychoeducation, and even promoting useful tools for emotional self-regulation (such as meditation) can be ways of reaching people on a large scale that directly or indirectly affect everyone who lives in this environment. It doesn’t mean treating a third of a generation, but caring for the environments where these communities develop, so that they can have hope again.

Just as we control infectious diseases more with hygiene than with antibiotics, we need to think about attitudes that promote true “mental sanitation” in school environments.